Do constitutional guarantees for ethnic minorities’ political representation and influence satisfy ordinary minority citizens? In my article in Journal of Conflict Resolution, I find that targeted, ethnically-based rules reduce grievances most substantially, but also generate new discontent if minorities are treated unequally.

In 2007, Nepal’s government adopted an interim power-sharing constitution which formally ended its decade-long civil war. Yet, the very next day, it faced an increasingly violent protest movement. This was spearheaded by activists of the Madhesi minority who remained dissatisfied with the constitution’s inclusive guarantees. Specifically, they demanded explicit recognition and not just representation. A particular cause of frustration was their continuing exclusion from top-level government posts and absence of autonomy, while other groups, in contrast, enjoyed increasing rights. Another issue was the marginalized status of the Hindi language, which many Madhesi share with their more privileged kin in India.

This example illustrates the two arguments I make in this article. First, ethnic minority members do not evaluate their group’s political status in a vacuum. Instead, minorities also consider their group’s relative status, as compared to other groups. Second, much depends on how group representation is constitutionally “engineered”, especially in places that lack inclusive norms in the first place. This characterized Nepal after the end of its long-standing, exclusionary Hindu monarchy. Indeed, Madhesi protesters did not question the principle of power-sharing per se. Instead, they protested its specific institutional form and their low attainments under it, as compared to other Nepalese groups and to their kin in India.

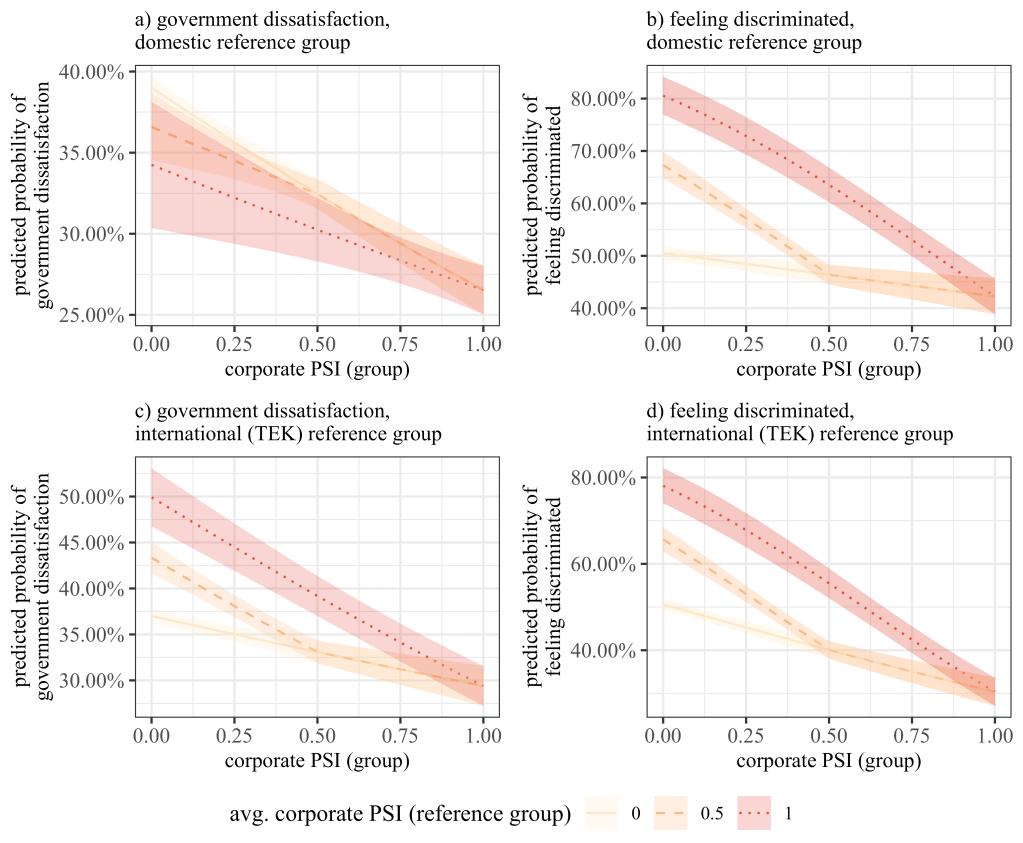

Expanding these arguments, I explain how the constitutional design of power-sharing rules affects ethnic minorities’ grievances. I argue that corporate power-sharing, based on constitutionally-enshrined and ethnically-based guarantees, alleviates minorities’ grievances most strongly. Its rigid, ethnically-based guarantees are not only comparably enforceable, but also protect a minorities’ future representation. However, by relying on explicitly group-differentiated criteria, corporate power-sharing also accentuates relative inter-group comparisons. In particular, minority members may remain dissatisfied even where they attain guarantees of representation, but where these guarantees fall short of the standards set by their domestic peers and transnational kin, as was the case for Nepal’s Madhesi.

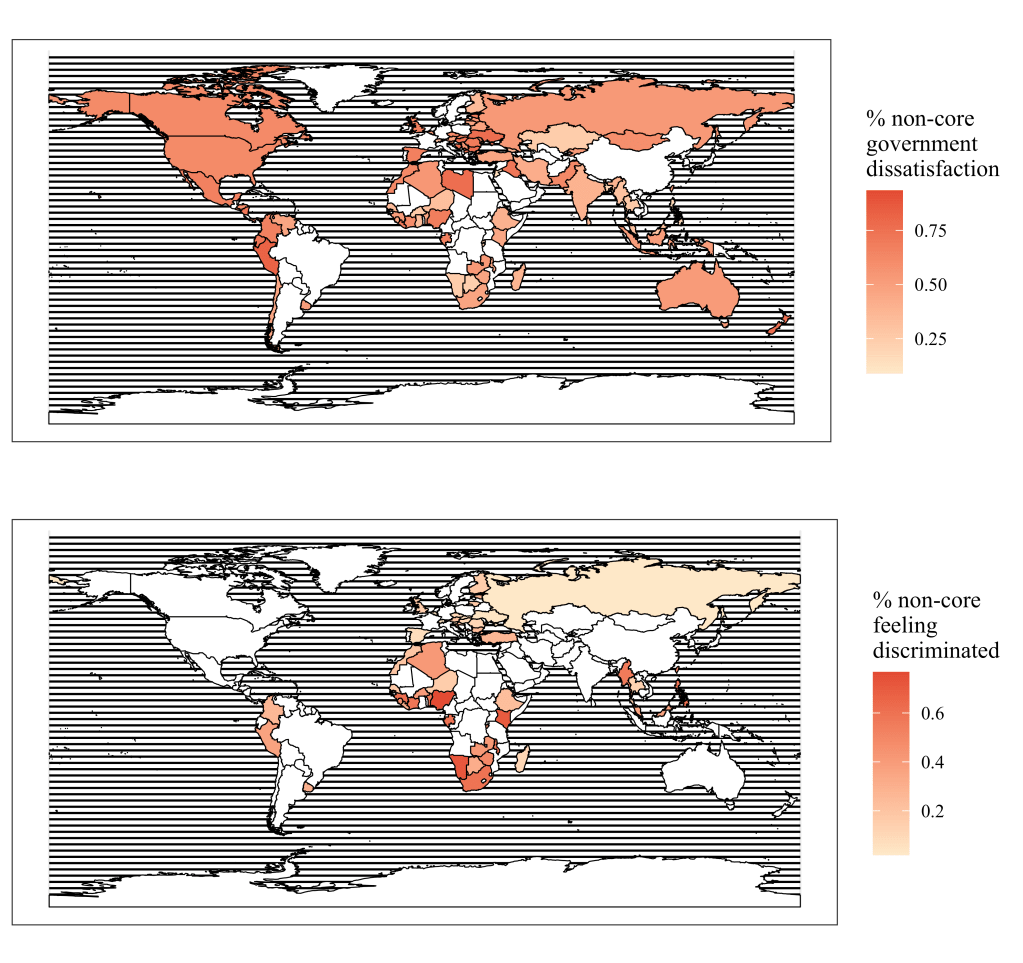

To test these expectations, I rely on my new SEAMS dataset, which is the most extensive, global collection of mass surveys used in the study of inclusive institutions so far. To capture minority grievances, I construct two dependent variables based on question items that tap into respondents’ attitudes towards government and their perception of being discriminated. I connect these with group-wise, time-varying information on ethnically-based power-sharing practices and institutions. The resulting data comprise 7260925 respondents, nested in 606 ethnic groups settling in 93 multi-ethnic countries between 1992 and 2018.

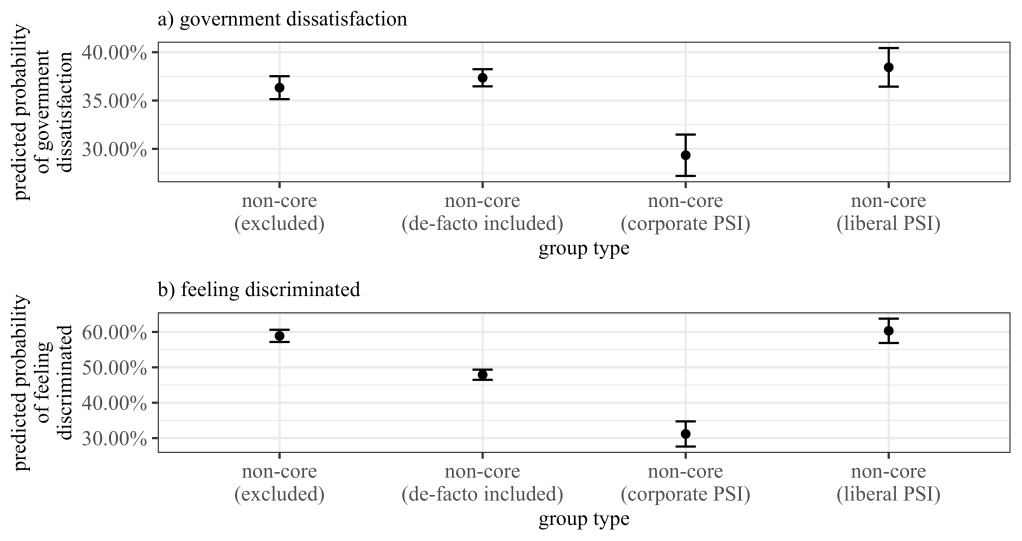

My results support my arguments. First, using hierarchical multi-level models, I find that corporate power-sharing reduces grievances more substantially than its informal and liberal alternatives. In additional group-level analyses, I examine the mechanisms driving this finding. These indicate that corporate power-sharing institutions not only guarantee that minorities initially attain representation, but also that these gains remain durable, which in turn substantially alleviates grievances.

Second, however, my multi-level models also indicate that minorities are more likely to form grievances where they attain relatively lower degrees of corporate power-sharing than their domestic ‘peers’ or their transnational kin groups. These findings are robust to alterations in the dependent variable, changes in sample composition, and a large battery of controls. They are also reflected in a group level measurement model approach, which combines my underlying question items into a latent variable tapping into group grievances.

These findings hold two key lessons for efforts to constitutionally engineer peace in multi-ethnic states. First, they indicate that ethnically-based power-sharing rules most substantially alleviate ethnic minorities’ grievances. Such rules not only offer the strongest guarantee for minorities’ political representation at any given point of time, but also increase the chance that these gains remain protected. In contrast, informal power-sharing reduces grievances less substantially, while liberal power-sharing rules do not appear to do so at all, at least as given by my measures. These findings underline case-based observations that minorities frequently require formal, enforceable reassurances and explicit ethnic recognition.

Second, however, I also find that ethnically-based power-sharing rules accentuate relative comparisons. I find that minorities may form grievances even where they attain substantial guarantees of representation, but where these guarantees remain below those given to other groups in the same country. This highlights the importance of offering similar guarantees to all groups, rather than restricting them to a select set of constituent groups.

For detailed findings and methodology, please check out the article here.

Inclusion, recognition, and inter-group comparisons: The effects of power-sharing institutions on grievances*†

Juon, Andreas (2023). Journal of Conflict Resolution (online first).

Description | PDF (Open Access) | Supplement | DOI