How does constitutional power-sharing affect the salience of ethnic identities? This question is critical, as salient ethnic divisions can increase the risk of political violence. It is hence no surprise that ethnic salience forms a cornerstone in debates on constitutional peacebuilding. Some observers argue that reducing ethnic salience is either unrealistic or only likely through accommodationist institutions. Hence, they recommend accommodating diverse ethnic groups, most notably through power-sharing. In contrast, critics warn that accommodation may harden ethnic divisions. Instead, they recommend integrative institutions that foster a single public identity. Given the centrality of ethnic salience to this debate, it is surprising how little empirical attention it has received in studies on the most widely advocated accommodative strategy, power-sharing.

In this article, I address this debate with a new theoretical argument, based on social psychological underpinnings, and a quantitative analysis that relies on new, systematic data on ethnic salience around the world.

Drawing on social psychology, I introduce a cognitive concept of ethnicity into the power-sharing literature. In this view, ethnic identities will be salient if they account for meaningful similarities and differences between ethnic groups and if they are, at the same time, readily available in individuals’ memory. Building on this conception, I theorize on two countervailing mechanisms whereby prolonged power-sharing affects ethnic salience. First, power-sharing gradually attenuates between-group inequalities, for instance in terms of representation and wealth. Thereby, it decreases their salience. Second, however, some types of power-sharing politicize individuals as ethnic group members, render ethnic identities more accessible, and thereby increase their salience. This second mechanism is closely tied to ethnically-based types of constitutional power-sharing. Based on these mechanisms, I expect prolonged power-sharing practices to reduce ethnic salience over time. However, this effect should be attenuated, and possibly reversed, if power-sharing rests on ethnically differentiated provisions.

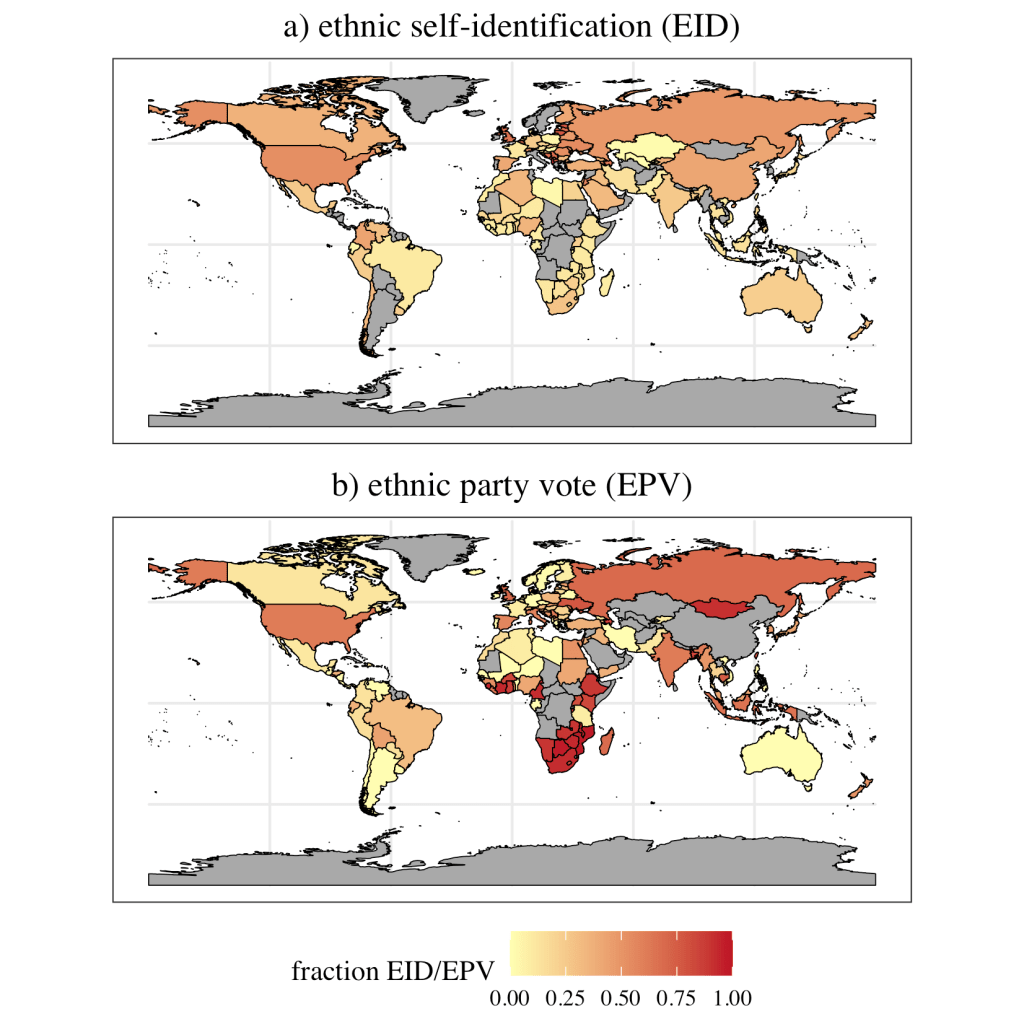

To test these arguments, I rely on new, globally representative survey data from my SEAMS database. I capitalize on two individual-level measures which capture two key aspects of ethnic salience: First, the degree to which individuals privilege their ethnic over their national identity; and, second, whether they intend to vote for ethnically based parties (see figure below). As the resulting sample encompasses more than 900,000 respondents from 132 diverse countries, my findings not only offer the first direct attitudinal evidence on the relationship between power-sharing and ethnic salience, but also contribute to a growing cross-national literature on ethnic salience more broadly.

In line with my argument, find that longer exposure to power-sharing practices, proxied by joint representation of multiple groups in the executive, is associated with reduced ethnic salience. This association is most pronounced for informal forms of power-sharing, such as ad-hoc electoral pacts. In contrast, ethnically differentiated power-sharing institutions are associated with increased ethnic salience (see figure below). All my specifications incorporate fixed effects at the ethnic group year-level. Hence, my findings are unlikely endogenous to a pattern whereby power-sharing is provided to groups with the most salient identities in the first place.