To safeguard peace, numerous multiethnic countries adopt territorial autonomy, for instance in the form of federalism or decentralization. However, there is increasing concern that territorial autonomy can generate new violence at the subnational level. For instance, in several of India’s federal states, extreme nativist movements have campaigned for the exclusion of non indigenes from local representation and economic opportunities. In turn, this has generated pervasive discontent and repeatedly sparked deadly riots. Violent clashes between regionally dominant and non-dominant groups have also erupted in many other federal and decentralized states and regions, including Indonesia’s Aceh, Uganda, Nigeria, and Ethiopia. Does territorial autonomy, rather than reducing ethnic violence, redirect it to the subnational level?

In this article, I address this question. I proceed from the observation that territorial autonomy provides important benefits to ethnic groups that control the subnational government. These may profit from overrepresentation in the regional administration, disproportionate influence over its policies, and privileged access to economic goods, including land, resource rents, and jobs. This generates tensions between them and other groups that remain excluded from regional government.

However, not all tensions between regionally dominant and non-dominant groups escalate into violence. As my findings show, the violent escalation of subnational tensions is far more likely, if ethnic representation in the national government is unequal. If representation favors those groups that are marginalized at the regional level, their leaders may employ violence to provoke government intervention in their support. Conversely, if national government representation favors the same groups that also control the regional government, their leaders will be especially uninhibited in monopolizing political power and economic resources within their regions. In turn, this generates especially combustible grievances among their disadvantaged peers and increases the risk of episodic mass-driven violence.

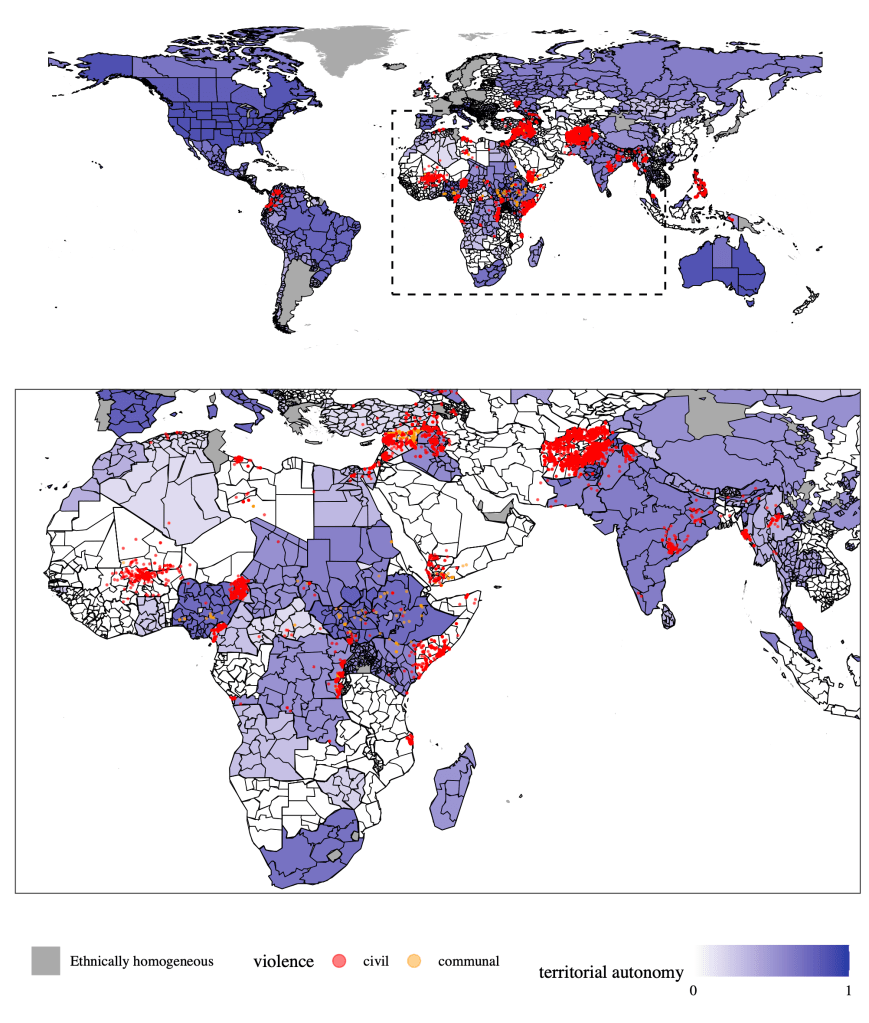

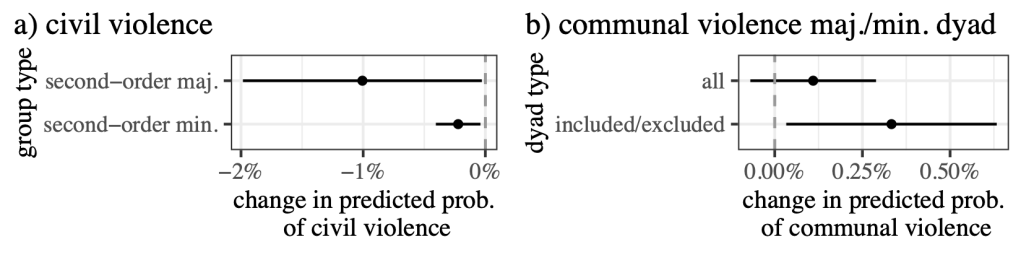

My evidence for these arguments is based on a comprehensive quantitative analysis that comprises all subnational regions in all multi-ethnic countries between 1989 and 2019 (see figure above). I find that groups in highly autonomous regions are less likely to engage in rebellions against the national government (“civil violence”), regardless of whether they control the regional government. Hence, the pacifying consequences of autonomy extend even further than previously acknowledged. However, territorial autonomy conversely increases the risk of localized, communal violence between regionally dominant and non-dominant groups (see figure below). In line with my argument, these risks are especially pronounced, if national government representation is unequal. This underlines warnings that territorial autonomy may shift violence to the subnational level. Yet, it suggests that these risks can be countered by broad-based inclusion in the national government.

I corroborate these findings with additional analyses. First, an instrumental variables analysis indicates that my findings are unlikely due to strategic considerations whereby autonomy is tailored with respect to anticipated violence. Second, I demonstrate that autonomy affects group-wise economic attainments, one-sided violence, grievances, and developments during subnational conflicts as implied by my argument (see figure below). Finally, I trace the intermediate steps of my argument in three influential cases: Sindh province in Pakistan, Jonglei state in South Sudan, and Ondo state in Nigeria.

As my measures are based on de jure institutions, my findings highlight important institutional recommendations. Most importantly, where territorial autonomy is adopted as a peace-building tool, it needs to be combined with national-level power-sharing to alleviate tensions in ethnically diverse regions. A second remedy highlighted in this study is subnational power-sharing, whereby diverse groups commit to sharing power and economic resources in the regional government. In diverse contexts, including Kenya and Nigeria, such arrangements have demonstrably helped to defuse ethnic tensions generated by territorial autonomy.

For detailed findings and methodology, please check out the article here.

Territorial autonomy and the trade-off between civil and communal violence

Juon, Andreas (2024). American Political Science Review. | Description | PDF | Supplement | DOI

| Description | PDF | Supplement | DOI