There is mounting evidence that sharing power with ethnic minorities helps avert violent conflict. However, proposals to constitutionally entrench power-sharing, for instance through government quotas, remain controversial. Constitutional power-sharing best addresses minorities’ demands for durable guarantees. Yet, it can also foster new discontent among disadvantaged minorities, generate a backlash from the formerly-dominant majority community, and deepen ethnic divisions. Thereby, it risks establishing polarized societies which face democratic shortcomings and the specter of renewed conflict. Does constitutional power-sharing prevent ethnic civil war at the cost of losing the peace?

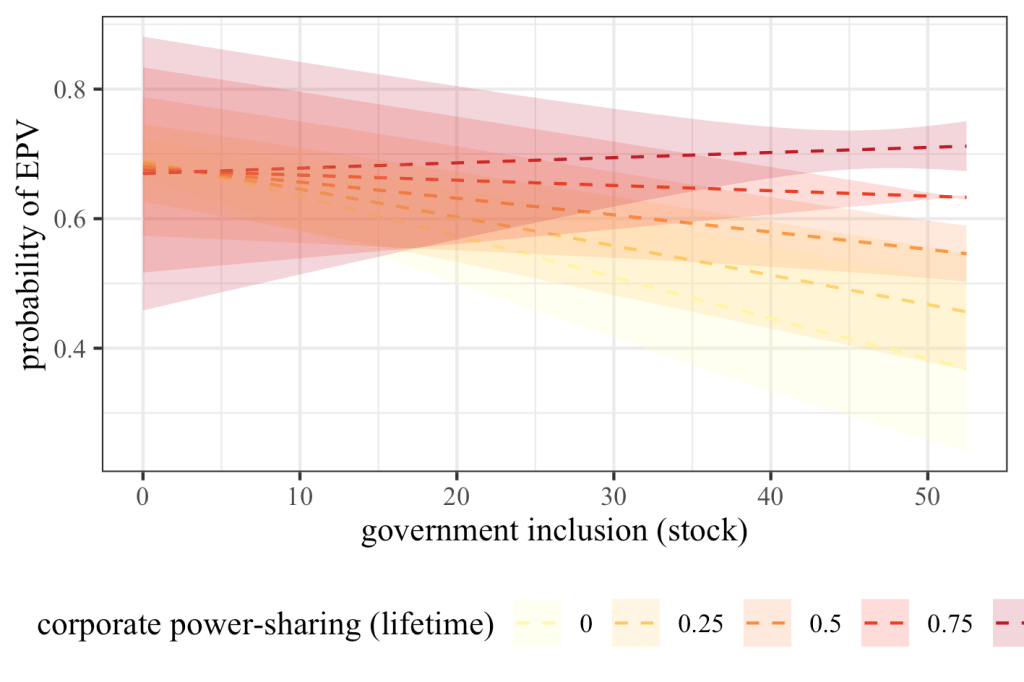

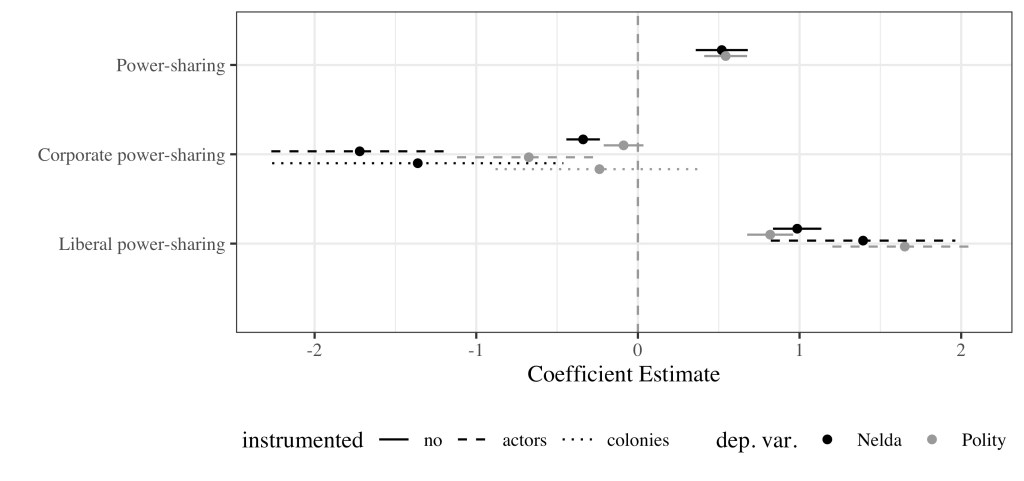

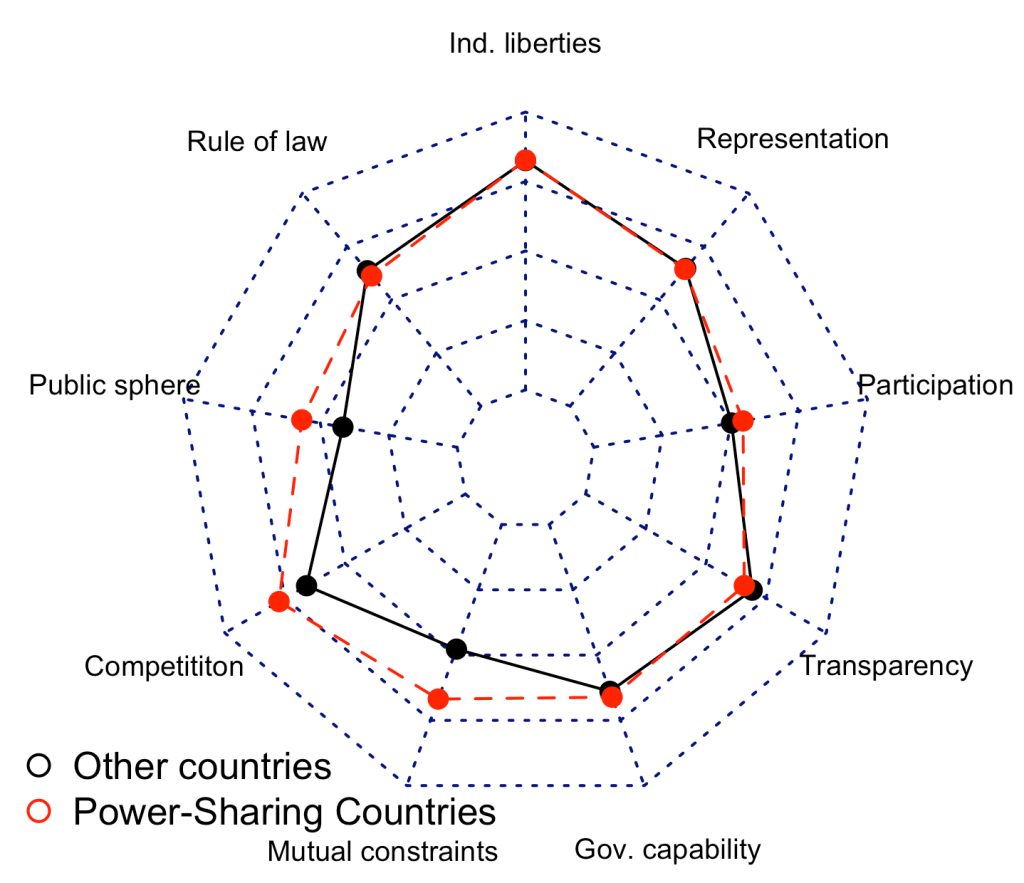

I address this debate with new theory, new data, and new evidence. While existing cross-national research predominantly focuses on broad types of de facto power-sharing and on extreme violence, I examine specific constitutional rules and systematically consider both their direct effects on civil war risks, as well as their “side-effects”, including on the political attitudes of ordinary citizens. My findings show that ethnically-based power-sharing rules most substantially alleviate minorities’ discontent and hence reduce the risks of civil war. However, they come with important drawbacks: in particular, ethnically-based power-sharing rules are especially likely to generate discontent among relatively disadvantaged minorities, provoke resentment among the majority community, and perpetuate ethnic polarization. In turn, it can harm important democratic qualities and engender destabilizing backlashes.

Specifically, the project’s main contributions are as follows:

- First, I introduce the new Constitutional Power-Sharing Dataset (CPSD), which enables me to systematically test the merits of different types of power-sharing. This new global database provides comprehensive information on constitutional power-sharing rules in 181 countries since the end of World War II. Importantly, it distinguishes between the two most widely-used, yet controversially discussed types of power-sharing: an ethnically-based (“corporate”) type on the one hand (e.g., Bosnia, Lebanon, Belgium) and a formally group-blind liberal type on the other (e.g., Switzerland, post-apartheid South Africa, post-Hussein Iraq). This enables me, and future researchers, to assess how specific constitutional rules affect minorities’ political outcomes, various group’s political attitudes, and societal outcomes, including democracy and ethnic conflict.

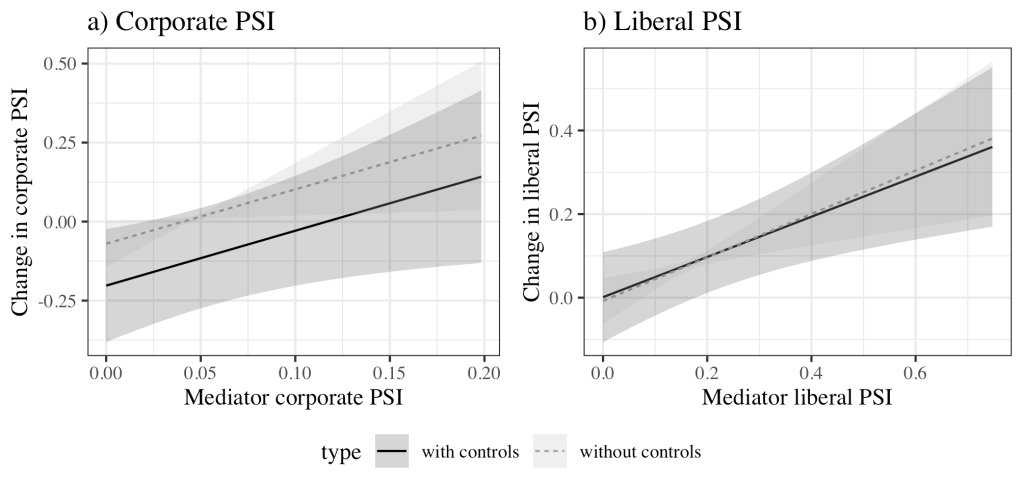

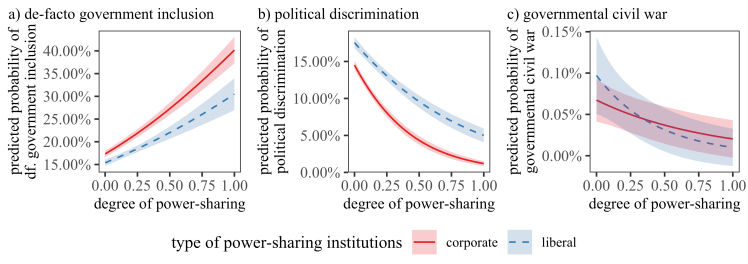

- Second, using this data, I provide urgent, policy-relevant evidence on the effects of different constitutional power-sharing rules on democracy and ethnic conflict. My findings indicate that constitutional power-sharing strongly improves the representation of minorities and alleviates their political discontent (Juon 2020; Juon 2023). Moreover, in two publications co-authored with Daniel Bochsler, I show that constitutional power-sharing improves democratic quality, with surprisingly few drawbacks (Bochsler & Juon 2021). However, only liberal power-sharing rules consistently improve overall democracy levels, while ethnically-based rules exhibit more mixed effects (Juon & Bochsler 2022).

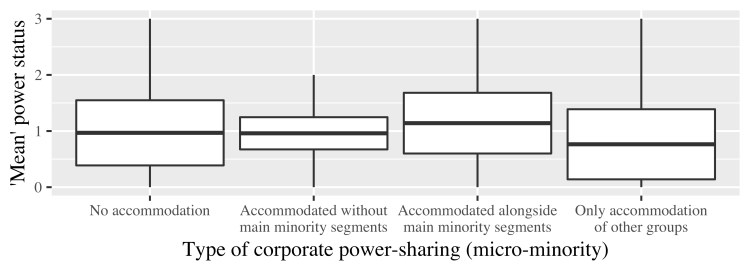

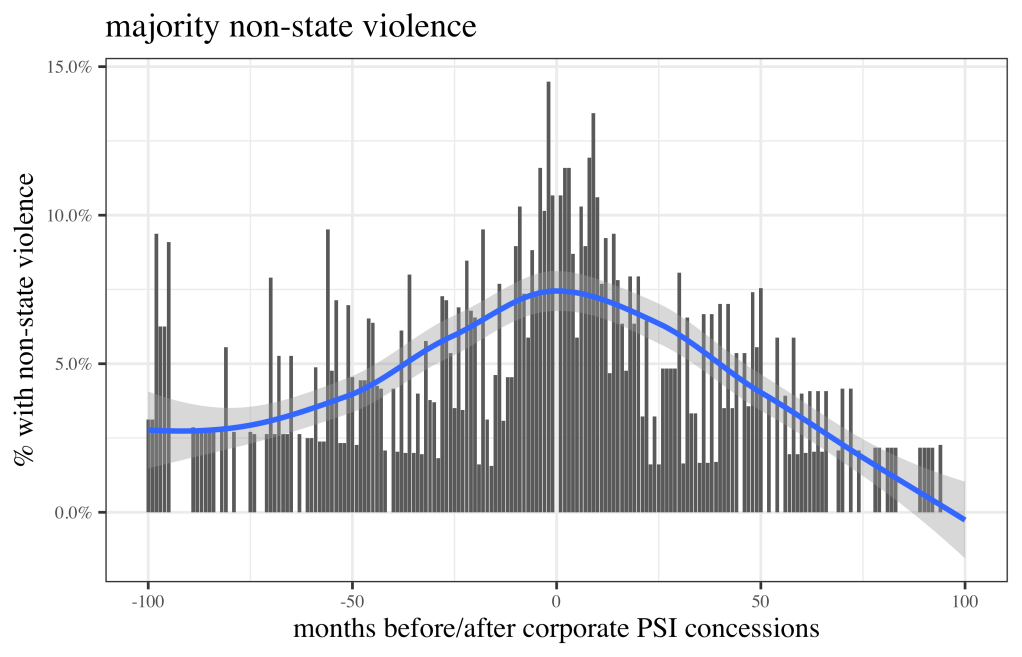

- Third, I examine the risk that constitutional power-sharing generate a backlash from societal groups that do not directly profit from its inclusive guarantees. Despite the beneficial consequences of constitutional power-sharing (see above), such a backlash can undermine peace and stability in the long-term. Worryingly, my findings indicate that ethnically-based power-sharing rules improve the situation of larger minorities, but further diminish the representation of micro-minorities (Juon 2020). I also find that such rules can generate new discontent among relatively disadvantaged minorities more broadly (Juon 2023) and that they can spark amajoritarian backlash, where the majority community perceives ethnic power-sharing as violating norms of majority rule and individual equality (Juon, conditionally accepted).

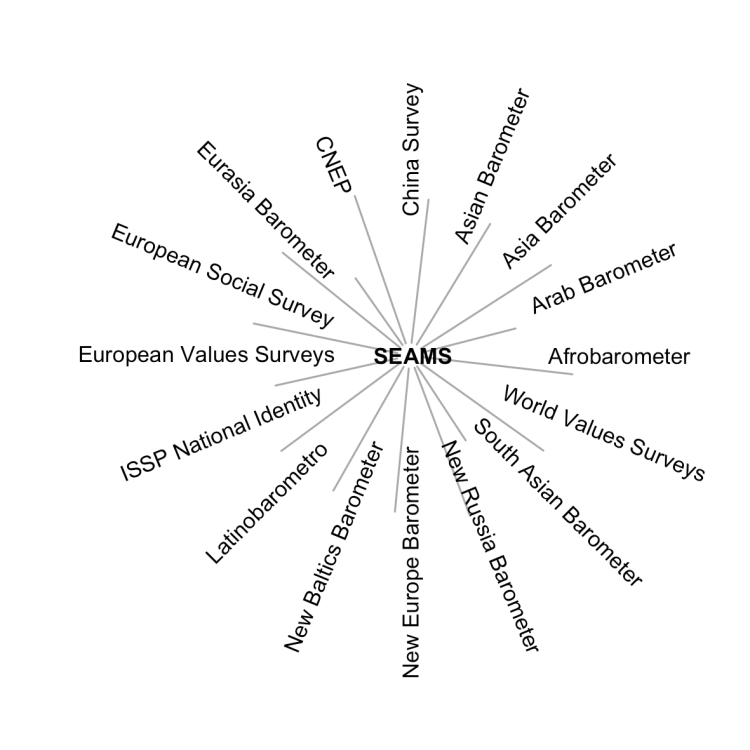

- Finally, I provide systematic evidence on how constitutional power-sharing affects ordinary citizens’ political attitudes. Thereby, I go beyond the elite focus of most previous cross-national studies of power-sharing. To set up such an analysis, I have assembled SEAMS, a database of standardized, ethnically attributed mass surveys that covers more than 2 million respondents in 148 countries. My findings show that ethnically-based power-sharing rules most substantially reduce minority discontent (Juon 2023). However, these rules also make it more likely that citizens privilege their ethnic over their national identities and vote for ethnic parties. Thereby, they contribute to ethnic polarization in the long-term (Juon Online First).

Please click on the publications’ descriptions and dataset links below to learn more about these contributions.

Related publications

The long-term consequences of power-sharing for ethnic salience

Juon, Andreas (Online First). Journal of Peace Research. | Description | PDF | Supplement | DOI

| Description | PDF | Supplement | DOI

Inclusion, recognition, and inter-group comparisons: The effects of power-sharing institutions on grievances

Juon, Andreas (2023). Journal of Conflict Resolution 67 (9): 1783-1810. | Description | PDF (Open Access) | Supplement | DOI

| Description | PDF (Open Access) | Supplement | DOI

Democracy promotion through power-sharing: The role of mediators’ constitutional templates

Bochsler, Daniel & Juon, Andreas (2023). In Simon Geissbühler (Ed.): Democracy and Democracy Promotion in a Fractured World. Challenges, Resilience, Innovation. Berlin/Zürich: LIT Verlag. | Link

| Link

The two faces of power-sharing

Juon, Andreas & Bochsler, Daniel (2022). Journal of Peace Research 59 (4): 526-542. | Description | PDF (Open Access) | Supplement | DOI

| Description | PDF (Open Access) | Supplement | DOI

Power-sharing and the quality of democracy

Bochsler, Daniel & Juon, Andreas (2021). European Political Science Review 13 (4): 411-430. | Description | PDF | Supplement | DOI

| Description | PDF | Supplement | DOI

Minorities overlooked: Group-based power-sharing and the exclusion-amid-inclusion dilemma

Juon, Andreas (2020). International Political Science Review 41 (1): 89-107. | Description | PDF | Supplement | DOI

| Description | PDF | Supplement | DOI

Ongoing work

Terminating the war, losing the peace? Constitutional power-sharing and its discontents

Juon, Andreas (book manuscript). Under review. | Description (PDF)

| Description (PDF)

Ethnic accommodation and the backlash from dominant groups

Juon, Andreas (Online First). Journal of Conflict Resolution.

| Description | PDF | Supplement | DOI

| Description | PDF | Supplement | DOI

The survival and collapse of constitutional peacebuilding, 1945-2018

Juon, Andreas (WP4). First draft under preparation.

Related data

Constitutional Power-Sharing Dataset (CPSD)

As part of my projects on power-sharing and regional autonomy, I have created the Constitutional Power-Sharing Dataset (CPSD). This dataset contains detailed indicators on formal power-sharing provisions found in state constitutions and autonomy statutes targeting politically significant ethnic minorities. The current version (v.1.2) codes institutions mandating the inclusion of minorities into national government as well as providing them with influence over political decision-making. It contains data for minorities settling in 174 countries and for the time period between 1945 and 2016. I have finished collecting a new, thoroughly updated version of the CPSD. This will encompass significantly more group years (~180 countries, 1945-2018). Future versions will extend the coverage to other forms of constitutional peacebuilding, including regional autonomy, economic accommodation and cultural recognition. An interactive dashboard enabling researchers and the public to explore constitutional peacebuilding efforts since World War II more broadly is in development.

Standardized Ethnically Attributed Mass Surveys (SEAMS)

The Standardized Ethnically Attributed Mass Surveys (SEAMS) dataset integrates a large number of global and regional mass surveys, such as the World Values Surveys and the Afrobarometer. It serves two purposes. First, it provides standardized information for major public opinion concepts, for instance on (dis-)satisfaction with government institutions, vote intentions, ethnic identification, and perceptions of belonging to a discriminated group. Second, it provides systematic information on survey respondents’ ethnicity, region of residence, language, religion, and phenotype, which is linked to existing datasets, including EPR and CPSD. Thereby, it enables researchers to study how time-varying country- or group-level variables (such as democratization, GDP growth, and ethnic power-sharing) affect public opinion and vice versa. The current version (v1.1) integrates information from 98 unique survey waves, which together cover 2’071’315 respondents nested in 1372 country years and 148 countries. Future releases will add more variables (e.g., on left-right identification), surveys, and information on the heterogeneous question items underlying SEAMS’ standardized variables.